Bulimia Nervosa Disorder

*** Disclaimer: The following article includes information derived from our clinical team’s impressions as specialized professionals working directly with Eating Disorders in Windsor/Essex County.

Bulimia Nervosa is an eating disorder that is quite often misunderstood. While the general public typically believes bulimia to be exclusively binge eating following by vomiting, the diagnosis actually includes alternative forms of purging behaviour that often go overlooked.

In the 2018-2019 year, BANA collected data on our active clients to determine how frequent each eating disorder diagnosis is in the Windsor/Essex community. What we found is that Bulimia Nervosa is the most frequently diagnosed eating disorder, at a rate of approximately 56.7%. It is important to remember that embarrassment, shame, hiding and secrecy are highly enmeshed in symptoms of Bulimia Nervosa; therefore, the disorder can often be overlooked by loved ones, medical professionals or the individuals themselves.

The 5th rendition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM-5) is the current guideline used in North America to diagnose all mental health disorders. It outlines the requirements that must be met in order to receive any diagnosis within its pages.

DSM-5 CRITERIA FOR BULIMIA NERVOSA

a) The individual is experiencing recurring episodes of binge eating ; binge eating is characterized by the following:

- Eating an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period time under similar circumstances; this is done within a discrete period of time, typically within a 2-hour period

- There is a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode; feelings of being unable to stop or control how much one is eatin

b) Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours that are used to prevent weigh-gain; typically referred to as purging behaviours. These can include self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics or other medications (such as diet pills), fasting/dieting, and excessive exercise

c) The binge eating and compensatory behaviours both occur at least once a week (on average) for 3 months

d) The way the individual evaluates themselves is unduly influenced by body shape and weight

e) The disturbance does not occur during episodes of anorexia nervosa

Severity Ratings: based on the frequency of compensatory behaviours

Mild = average of 1-3 compensatory behaviours/week

Moderate = average of 4-7 compensatory behaviours/week

Severe = average of 8-13 compensatory behaviours/week

Extreme = average of 14 or more compensatory behaviours/week

BINGING VS. OVEREATING

Often at BANA, we hear some confusion surrounding what constitutes a binge. For diagnosis, it is required that the portion size is objectively large, meaning most people would agree that is too much food to have within a given period of time. However, some people experience subjective binges, where not everyone agrees that the portion meets criteria but it is larger than what individual typically eats. In the case of subjective binges, the individual themselves feel out of control despite portions not being excessive. Beyond objective and subjective binges, there is overeating. Overeating may only be slightly more food than what is typical; however, the individual may not feel out of control. Overeating is a relatively normal behaviour, as most of us likely overeat from time-to-time.

Below is a small chart that can help outline these differences.

Type: Portion: Control:

Objective Binge Definitely large Out of control

Subjective Binge Not agreeably large Out of control

Over-Eating Not agreeably large In control

COMPENSATORY BEHAVIOURS (AKA: PURGING)

Compensatory behaviours – also referred to as purging behaviours – are methods individuals use to make up for having binged, overeaten, or having a food that contradicts their dietary rules. Compensatory behaviours have the goal of trying to prevent eating from influencing weight/shape. All compensatory behaviours come with significant health risks and could be life-threatening – some resolve with recovery, while others can be permanently damaging. It is important to note that if you are engaging in any compensatory behaviours, we recommend visiting your primary health practitioner regularly to investigate these health risks.

Compensatory behaviours are typically the most misunderstood criteria of Bulimia. As society changes, professionals in the field of eating disorders may notice new compensatory behaviours arise that were not considered before. Although the DSM-5 does not include excessive use of supplements, chronic use of shape-wear, or utilizing caffeine, cigarettes or other substances for weight-control purposes, these may be considered in future editions (of course, this is only speculation).

Beyond self-induced vomiting, individuals may misuse laxatives, diuretics or other medications to attempt to control their weight/shape. It is important to note that these medications serve an important medical purpose; however, when not used as prescribed or for medical purpose, they can be considered disordered.

Three compensatory behaviours that are noticeably on the rise in today’s society are dieting, fasting and excessive exercise. Although diets are a definite precursor of eating disorders – an overwhelming majority of our clients have a long history of yo-yo dieting – not everyone who diets has or will have an eating disorder. Although dieting is always considered in the diagnostic process, we will not cover it in this article. Dieting is a complex phenomenon, one that requires a great deal of education and discussion. Much of the researched-based, empirical information on dieting is contradictory to what the general public believes; often, our anti-diet stance is met with defensiveness and reservation. Therefore, we will address dieting separately in its own article.

We see that more and more, fasting is included in many diets – essentially, efforts to delay eating as long as possible. Fasting meets Bulimia criterion when the individual uses it as a response to having “mis-eaten”. For example, if the individual binged the evening before, they may fast as long as possible the next day to “make up for last night’s binge”. Compensatory fasting is typically required to occur for a minimum of 8 wake hours to meet the diagnostic criteria.

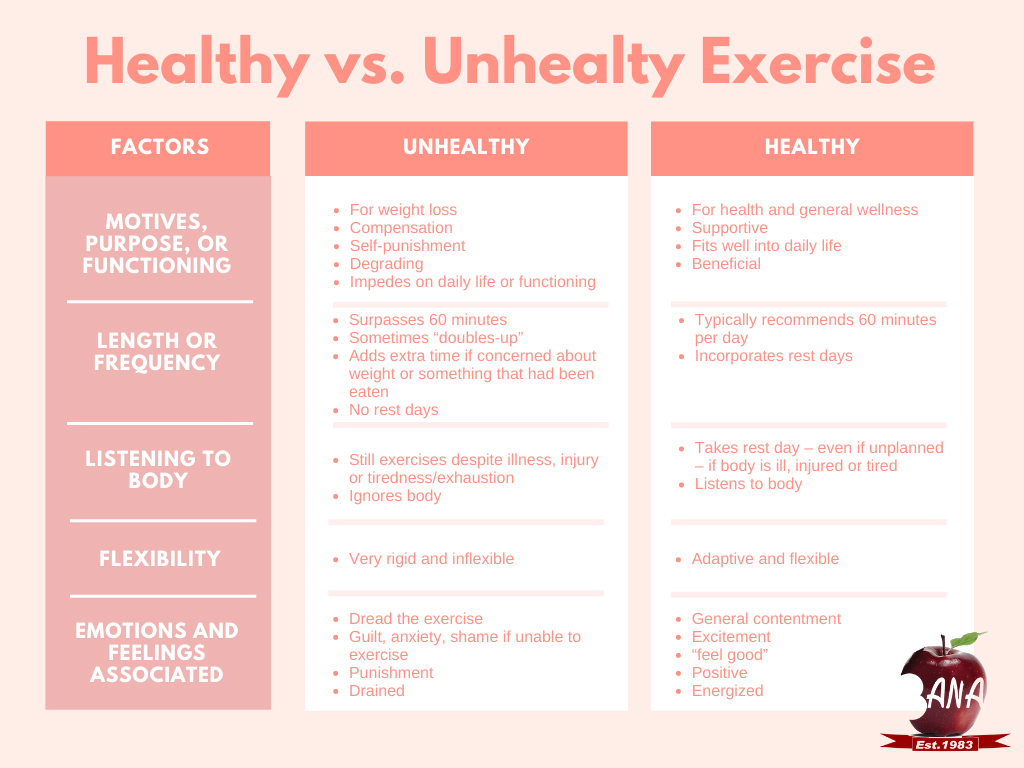

Excessive exercise is a hot topic, and one that is faced with a lot of defense and debate. In society today, fitness has become very “in”, and many face pressures to engage in excessive or rigid exercise in order to “fit in”. Of course societal standards of “the ideal body” currently reflect toned and muscular physiques, making driven exercise even more compelling. It is a well-researched fact that exercise is an important factor in mental and physical health. Exercise crosses over to unhealthy and disordered when motives, thoughts and behaviours become degrading rather than supportive. Arguably, motives for exercise should be health directed, rather than solely weight-focused. Excessive exercise may incorporate longer-than-recommended periods of engagement (for example: going to the gym two times a day for an hour each visit, or adding an extra 45 minutes to your routine after you’ve had a binge). If individuals are still engaging in exercise, despite illness or injury, this is also seen as disordered. Other markers of excessive exercise are when one is dreading the exercise; feels guilt/shame/anxiety if unable to exercise; utilizes it as a form of self-punishment; and/or allows exercise to disrupt functioning or daily life. It is important to regularly check in with yourself, and your thoughts and motives behind the exercise you engage in. At BANA, we frequently see clients who have a bulimia diagnosis on the basis of this compensatory behaviour – however, it is often overlooked or excused away by the general public.

THE WEIGHT MYTH

Contrary to popular belief, Bulimia Nervosa is difficult to spot. Unlike Anorexia Nervosa, where clients may be noticeably underweight or emaciated, most individuals who have been diagnosed with Bulimia are of normal to above-average weight. In fact, weight is the primary difference between the diagnoses of Bulimia Nervosa and Anorexia Nervosa – Binge/Purge Subtype.

OVERVIEW

Bulimia Nervosa is very often misunderstood, and many individuals may find it difficult to identify symptoms. If any of the criteria outlined in this article hit-home, but you’re not sure if they meet all the requirements for a diagnosis, do not hesitate to contact us through general intake. We can meet with you to discuss potential symptoms, and can support you through some of your concerns.

Our general intake number is: 1-855-969-5530

RESOURCES:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Centre for Clinical Interventions. (2018). Unhealthy exercise. Retrieved from https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/

Centre for Clinical Interventions. (2018). What are eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/

Centre for Discovery: Eating Disorder Treatment. (2019). Four common misconceptions about bulimia nervosa. Retrieved from https://centerfordiscovery.com/blog/four-common-misconceptions-bulimia-nervosa/